- Home

- Abraham Karpinowitz

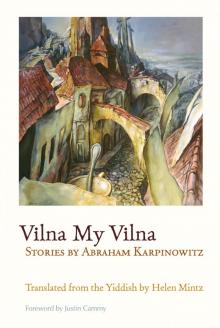

Vilna My Vilna

Vilna My Vilna Read online

Other titles in Judaic Traditions in Literature, Music, and Art

Bridging the Divide: The Selected Poems of Hava Pinhas-Cohen

Sharon Hart-Green, ed. and trans.

Early Yiddish Epic

Jerold C. Frakes, ed. and trans.

Letters to America: Selected Poems of Reuven Ben-Yosef

Michael Weingrad, ed. and trans.

My Blue Piano

Else Lasker-Schüler; Brooks Haxton, trans.

Rhetoric and Nation: The Formation of Hebrew National Culture, 1880–1990

Shai P. Ginsburg

Social Concern and Left Politics in Jewish American Art: 1880–1940

Matthew Baigell

The Travels of Benjamin Zuskin

Ala Zuskin Perelman

Yiddish Poetry and the Tuberculosis Sanatorium: 1900–1970

Ernest B. Gilman

English translation Copyright © 2016 by Helen Mintz

Syracuse University Press

Syracuse, New York 13244-5290

All Rights Reserved

First Edition 2016

161718192021654321

∞ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

For a listing of books published and distributed by Syracuse University Press, visit www.SyracuseUniversityPress.syr.edu.

ISBN: 978-0-8156-3426-3 (cloth)

978-0-8156-1060-1 (paperback)

978-0-8156-5352-3 (e-book)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Karpinowitz, Abraham. | Mintz, Helen, translator.

Title: Vilna my Vilna : stories / by Abraham Karpinowitz ; translated from the Yiddish by Helen Mintz ; foreword by Justin Cammy.

Description: First edition. | Syracuse, New York : Syracuse University Press, 2015. | Series: Judaic traditions in literature, music, and art | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015037080| ISBN 9780815634263 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780815610601 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780815653523 (e-book)

Classification: LCC PJ5129.K315 A2 2015 | DDC 839/.134—dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015037080

Manufactured in the United States of America

Contents

List of Illustrations

Foreword JUSTIN CAMMY

Translator’s Note

Acknowledgments

Introduction HELEN MINTZ

1.Vilna without Vilna

2.The Amazing Theory of Prentsik the Shoemaker

3.The Red Flag

4.Shibele’s Lottery Ticket

5.The Folklorist

6.Chana-Merka the Fishwife

7.Lost and Found

8.Vladek

9.The Lineage of the Vilna Underworld

10.Jewish Money

11.Tall Tamara

12.The Great Love of Mr. Gershteyn

13.The Tree beside the Theater

14.Memories of a Decimated Theater Home

15.Vilna, Vilna, Our Native City

Maps

Glossary of People, Places, Terms, and Events

Story List with Original Publication

Bibliography

Illustrations

Figures

1.“Rubinshteyn the Folklorist set off for the fish market to collect material”

2.“Vladek grew up with us”

3.“You find yourself walking down a vaulted street”

Maps

1.The synagogue courtyard and surrounding streets.

2.Vilna and the surrounding area.

Foreword

Jewish intellectuals and writers have written about Vilna since the origins of modern Yiddish literature. If the historical shtetl was appropriated by the generation of classic writers who emerged in the mid- to late nineteenth century as the mythopoetic center of a new literature in need of its own native ground, for the writers that followed, the Jewish city was the setting from which to symbolically stage the confrontation between Jewishness and Europeanness, tradition and secularization, and to engage the challenges of class stratification, urbanization, the new politics of the Jewish street, and the competing languages of contemporary Jewish experience.

This volume of stories by Abraham Karpinowitz (1913–2004; Avrom Karpinovitsh in Yiddish) situates its narratives of interwar Jewish life in the author’s hometown of Vilna, with special attention to extraordinary characters from among the city’s ordinary street people. They are in conversation with a long tradition of Jewish writing about Vilna that sought to construct, challenge, interpret, and redefine a specific cultural myth of Jewish urban space. Insofar as Karpinowitz found his literary voice only after Vilna’s destruction, he also must be read within the broader context of Holocaust literature, specifically within the subcanon of Yiddish texts that spoke to a global readership that had suddenly lost its Yiddish-speaking heartland. One senses that Karpinowitz approached his writing as a sacred duty, in which the personalities he encountered as a young man were reanimated to resist the finality of their destruction. Their vibrant presence and life impulse is Karpinowitz’s preferred mode of post-Holocaust witnessing. While Abraham Sutzkever and Chaim Grade, the most famous of Vilna’s young Yiddish writers to survive the war, honed a highbrow literary aesthetic in their postwar engagement with their hometown, Karpinowitz found his talents best suited to a popular idiom. Vilna’s Yiddish-speaking alleys, brothels, taverns, and street corners would find their voice in him.

Given that Abraham Karpinowitz departed Vilna in 1937, drawn as a twenty-four-year-old to Stalin’s Jewish autonomous region in Birobidzhan, and then spent the war years in the Soviet Union, his confrontation with the completeness of his community’s destruction upon his brief return to Vilna in 1944 was all the more shocking. He had not lived through the final years of Polish rule, when the struggle for Jewish rights against nationalist xenophobia reached its peak, nor the city’s occupation under the Soviets when Jewish political and cultural expression was severely curtailed, nor its liquidation under the Nazis. His imagination remained frozen in the heyday of Vilna’s cultural dynamism. Soon after arriving in the new state of Israel from a Cypriot Displaced Persons camp in 1949, he joined the short-lived Yiddish literary group Yung-Yisroel (Young Israel). For the next three decades, in his spare time as manager of the Israeli Philharmonic Orchestra, his literary attentions would alternate between stories of Vilna and tales of life in Israel. Writing allowed him to navigate the distance between an organic Yiddish-speaking world dortn (over there) and the new politico-cultural landscapes of the Hebrew-speaking state in which Yiddish was permitted to exist publicly only on the margins. With this in mind, it is no coincidence that Karpinowitz’s first story in Di goldene keyt, the flagship journal of Yiddish literature and culture in Israel, was titled “Never Forget.”1

Avrom Karpinovitsh, “Farges nit,” Di goldene keyt 7 (1951): 174–79. The story appeared in a section dedicated to “young Yiddish literature in Israel,” a group of recently arrived writers who, under the encouragement of Di goldene keyt’s editor Abraham Sutzkever, formed the nucleus of the Yiddish literary group Yung-Yisroel in the 1950s. The story was reprinted as the opening selection in Karpinowitz’s first book, Der veg keyn Sdom (The Road to Sodom, 1959), a volume focused on the years of Israel’s founding. In this story, a young man who escaped the slaughters in the ghetto is now an Israeli soldier whose conscience is haunted by the final Yiddish words of his mother when he comes face-to-face with his enemy: “Never Forget!” The story perfectly situates the competing imaginative claims on Karpinowitz that would define the remainder of his career as his prose alternated

between Vilna and contemporary Israeli settings. As coeditor of the 1967 Almanac of Yiddish Writers in Israel, he remained committed to the cultural imperative of Yiddish writing in Israel and to Yiddish literature’s integration of Israeli realities into its imaginative universe.

Vilna, Real and Imagined

Vilna, known affectionately as the Jerusalem of Lithuania, cultivated a myth of place in which layer upon layer of historical experience added to the city’s reputation as harbinger of the most important trends in Eastern European Jewish culture. Indeed, no other Jewish city in Eastern Europe maintained a level of attachment from its natives, expatriates, and visitors that compelled them to so lovingly advertise its achievements. To be fair, until the twentieth century, there were not many big Jewish cities in Eastern Europe that could rival Vilna’s religious and cultural pedigree. For all of Warsaw’s new demographic strength and Lodz’s industrial power, they lacked the deep tradition of which there was a surfeit in Vilna, which was already known as a city of sages in the seventeenth century. Vilna’s reputation was sealed through the towering rabbinic scholarship of its most famous resident, Elijah ben Solomon Zalmen, the Vilna Gaon (1720–1797). The Gaon’s example set Vilna’s standard for intellectualism, diligence, creative reinterpretation, and openness to worldly knowledge. By the nineteenth century, the city was home to many leading intellectuals, maskilim, proponents of the Jewish enlightenment, and also a center of Hebrew and Yiddish publishing. Both Yehuda Leib Gordon and Avraham Mapu, respectively the most important poet and novelist of the rebirth of modern Hebrew literature, were residents of the city. Later, Vilna was a staging ground for the development of Jewish political awakening. Not only was it the birthplace of the socialist Bund (the General Jewish Worker’s Union) in 1897, but it hosted early circles of Hovevei Zion (the Lovers of Zion) and was the organizational base for Mizrahi, the most important early Zionist religious party. By 1902, Vilna could also boast its own radical martyr in the person of Hirsh Lekert, punished for an attempt to kill Vilna’s tsarist governor. The city continued to break new ground in the realm of the competition of ideas by hosting Literarishe monatshriftn (Literary Monthly), the first Yiddish scholarly journal. When Vilna (now Wilno) was incorporated into the new Polish state following World War I, its standing as a center of popular and scholarly Yiddishism was confirmed by the decision to headquarter there the Yiddish Scientific Institute (Yidisher visnshaftlekher institut, or YIVO), the most advanced center for scholarship on the history and culture of Ashkenazic Jewry. Vilna’s civic pride, rooted in a respect for tradition and for the city’s pioneering spirit, inspired its intellectuals and writers to rally behind the concept of nusekh Vilne, the Vilna way. As Max Weinreich, the director of YIVO proudly proclaimed, “In Vilna there are no ruins, because aside from its traditions Vilna has a second virtue: momentum. It is a city of activism, of pioneering.”2 Or, in the words of a popular folk saying that distinguished between material and cultural security, “Go to Lodz for work, to Vilna for wisdom.”

Max Weinreich, “Der yidisher visnshaftlekher institut,” in Vilne: A zamlbukh gevidmet der shtot Vilne, ed. Yefim Yeshurin (New York: [n.p.], 1935), 323, 325.

A great deal of the city’s creative energy emerged from a specific cultural geography that allowed Jewish writers to map their desires into a reading of its urban space. Of course, it is important to remember that Vilna was not an imagined city but in fact several competing imagined cities, each claimed by a different national group. To the Poles it was Wilno, where Catholic pilgrims flocked to see the famous virgin in the Ostra Brama church and whose central hill was punctuated by three crosses. Its spiritual capital for Poles was magnified by the words of hometown poet Adam Mickiewicz, whose Romantic epic Pan Tadeusz claimed the city and its surrounding lands as native ground: “O Lithuania, my country, thou art like good health. I never knew till now how precious you were, till I lost you.” For Lithuanians, the city was Vilnius, where one of their own princes built his fortress on a local hill as the city’s founding act, the ruins of which remained one of its defining sites. Though the Jews could not boast ownership over its cathedral or churches, its fortress or hilltops, their geographic center was marked by the crooked lanes and distinctive archways of the traditional Jewish quarter, where streets were referred to by the city’s Jews according to their Yiddish names, many in memory of local personalities. At its center was the shulhoyf, a courtyard complex that boasted the Great Synagogue, many smaller prayer houses (including that of the Gaon), several communal institutions, a public bathhouse and old well, and a clock marking the time for prayer. The shulhoyf’s more traditional spaces later competed with those that attempted to bridge the divide between observant and modern Jews, such as the Strashun Library, bequeathed by a local benefactor in the late nineteenth century, whose reading room became a neutral, shared space for Jewish scholars and writers of all religious and political stripes. By the interwar period, the area was also a hangout for local toughs, actors, and writers, many of whom congregated in bohemian spaces like Fania Lewando’s vegetarian restaurant and the neighboring Velfke’s café. If the traditional Jewish quarter was the symbolic heart of the community, by the twentieth century it existed as only one axis in Vilna’s expanding geocultural matrix. Others included Pohulanke, a newer, well-heeled neighborhood with broad boulevards and tree-lined streets that attracted the city’s intellectuals and many of its newer communal institutions. The YIVO building, the Maccabi playing fields, the Jewish Health Protection Society, the library of the Society for the Promotion of Culture, and several modern Jewish schools were among the many institutions that were built there, beyond the tangled streets of the traditional Jewish quarter, to represent the contemporaneity of Jewish life in Vilna. Across the city’s iconic Viliye River was the hardscrabble neighborhood of Shnipishok, where many working-class Jews resided, including several of those who would go on to form the nucleus of the literary and artistic group Yung-Vilne (Young Vilna) in the 1930s. Karpinowitz’s boyhood and early twenties was lived within this Jewish matrix where past and present, traditional and secular Jews, workers and intellectuals, a Jewish underworld and burgeoning middle class, Yiddishists and Hebraists, Zionists, socialists, Territorialists, and Jewish communists argued the world and contributed to Vilna’s dynamic expression of Jewish popular and high culture. Since neither the city’s Polish nor Lithuanian residents constituted a majority of Vilna’s population, the linguistic and cultural assimilation that significantly affected Jews in other Eastern European cities was mitigated for Vilna’s Jewish population, allowing them to rally around their own languages and culture.

By the interwar period, nusekh Vilne’s self-promotion as both a defender and producer of contemporary Jewish culture was continuously deployed to distinguish the city from its biggest competitors. From the perspective of Vilna’s Yiddishists, the future of Eastern European Jewry rested upon several pillars of which their city was a prime example: pride in the Yiddish language and its distinct culture as evidence of the Jews’ status as a nation; a commitment to yiddishkeit as the manifestation of Jewish secular humanism; a sense of civic pride and ownership over a traditional past in which the Gaon could be claimed as a folk hero by even secular Jews; and a firm sense of do-ism (here-ness) that envisioned a Jewish future in situ, in the Eastern European heartland of Jewish life, rather than elsewhere. Vilna served as the citadel of this modern conception of Jewish nationhood.

The number of modern histories and anthologies designed to assert Vilna’s reputation suggest that the age of nationalism created a need among Eastern European Jews for a capital of an imagined Yiddishland as a way to press their own distinctiveness as a people. Pride of place drove Vilna’s admirers to advertise and celebrate its centrality. While it was still under the control of the tsars, these included the enlightenment writer S. Y. Fuenn’s Kiryah ne-emanah (The Loyal City, 1860) and Hebraist Hillel Steinschneider’s Ir vilnah (The City of Vilna, 1900). The community’s travails during World War I, when

it was briefly occupied by Germany, inspired Tsemakh Shabad and Moyshe Shalit’s Vilner zamlbukh (Vilna Anthology, 1916, 1918), Khaykl Lunski’s Fun Vilner geto: geshtaltn un bilder geshribn in shvere tsaytn (From the Vilna Ghetto: Portraits from Challenging Times, 1918), Zalmen Reyzin’s Pinkes far der geshikhte fun Vilne in di yorn fun milkhome un okupatsye (Chronicles the History of Vilna in the Years of War and Occupation, 1922), and Jacob Wygodski’s In shturem: Zikhroynes fun di okupatsye-tsaytn (Eye of the Storm: Memoirs of Occupation, 1926). These volumes shaped a local, popular historiography during a period of dissolution to assist in reconstruction and the preservation of collective memory. Efforts to promote the city’s reputation in the interwar period were taken up by Morits Grosman’s Yidishe Vilne in vort un bild (Jewish Vilna in Word and Image, 1925), Israel Klausner’s Toldot ha-kehilah ha-‘ivrit be-Vilnah (History of the Jewish Community of Vilna, 1938), A. Y. Grodzenski’s Vilner almanakh (Vilna Almanac, 1939), and Zalmen Szyk’s 1000 yor Vilne (One Thousand Years of Vilna, 1939), the last the most detailed Yiddish guidebook ever produced of a Polish-Jewish city. Even those who left Vilna behind claimed the city as an important lieu de memoire, as when Yefim Yeshurin published Vilne: A zamlbukh gevidmet der shtot Vilne (Vilna: An Anthology Dedicated to the City) in New York in 1935.3 Local patriotism manufactured the need to export an image of the city in which the richness and diversity of Jewish culture nurtured, sustained, and inspired its population. This might explain the tension between YIVO director Max Weinreich’s desire during the 1930s to promote Vilna as possessing “genius of place”4 and American Jewish historian Lucy Dawidowicz’s admission many years later that her exposure to the city’s contradictions “shattered my sentimental notions about the viability of the realm of Yiddish.”5 Of course, after World War II, the impulse to memorialize Jewish Vilna took on new urgency for its former residents. We see this not only in the immediate postwar effort to publish memoirs of the city’s last days but most impressively in the work of Leyzer Ran, whose three-volume Yerushalayim d’Lite (Jerusalem of Lithuania, 1968–1974) attempted to reconstruct the full cultural milieu of interwar Jewish Vilna through the careful collection and reproduction of photographs and documents. Karpinowitz’s literary engagement with Vilna after the war is indebted to this historical and anthological imagination that produced an image of Vilna as model Jewish urban space.

Vilna My Vilna

Vilna My Vilna